WASHINGTON — In the early 1970s, Addison Mitchell McConnell Jr., a young and intense Republican lawyer, strode into the political science class he taught at the University of Louisville.

He didn’t introduce himself to his students. He went straight to the chalkboard and scribbled.”I am going to teach you the three things you need to build a political party,” he said, and backed away to reveal the words: “Money, money, money.”

Three decades later, the teacher has mastered the lesson like few in history.

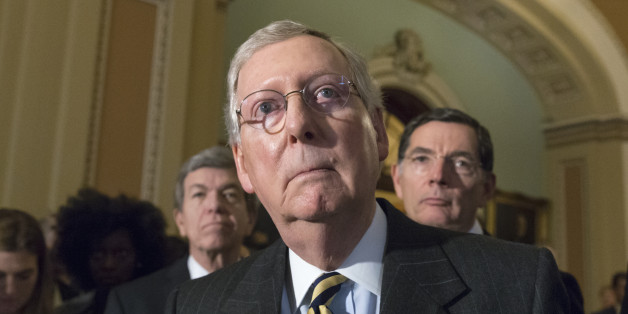

An extraordinary political fund-raiser, Senate Majority Whip Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., has used his skill to put himself on the brink of a remarkable career achievement. If Republicans hold the Senate in the Nov. 7 elections, he is expected to succeed retiring Sen. Bill Frist of Tennessee as majority leader.

McConnell’s rise to the top of Congress is testament to the power of money in modern politics. He has raised nearly $220 million over his Senate career; he spent the majority not on his own campaigns but on those of his GOP colleagues, who have rewarded him with power.

“He’s completely dogged in his pursuit of money. That’s his great love, above everything else,” said Marshall Whitman, who watched McConnell as an aide to Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., and as a Christian Coalition lobbyist.

A leader in the field of tapping the wealthy for campaign cash, McConnell also led the opposition against efforts to rein in such donations through campaign-finance reform — a fight that has taken him to the U.S. Supreme Court and put him toe-to-toe against another emerging Republican leader, presidential hopeful McCain.

A six-month examination of McConnell’s career, based on thousands of documents and scores of interviews, shows the nexus between his actions and his donors’ agendas. He pushes the government to help cigarette makers, Las Vegas casinos, the pharmaceutical industry, credit card lenders, coal mine owners and others.

Critics, including anti-poverty groups and labor unions, complain that McConnell has come to represent his affluent donors at the expense of Kentucky, the relatively poor state he is supposed to represent. They point, for example, to his support last year for a tough bankruptcy law, backed by New York banks that support him.

McConnell waves away all criticism of his fund-raising.

In a recent interview, he said he never allows money to influence him. His donors support him because they like his pro-business, conservative philosophy, he said, so it’s hardly proof of corruption when he does what they want.

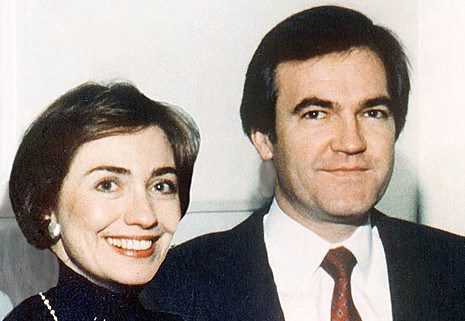

Supporters say, furthermore, that Kentucky benefits from having McConnell at the top, regardless of criticism over how he got there. McConnell uses his clout to steer millions of dollars to projects back home, said Steven Law, the senator’s former fund-raising aide, now top deputy to McConnell’s wife, Labor Secretary Elaine Chao.

Once he secured his own Senate seat, McConnell skillfully forwarded money to GOP senators who needed it, building a path to what he truly wanted — the No. 1 job.

McConnell is hardly alone in his quest for cash. Money cascades into politics these days. Senate races burned through $543 million in 2004, up nearly 50 percent from the previous election cycle. And although some argue that the power of political money can be corrupting — witness this year’s imprisonment of former U.S. Rep. Randy “Duke” Cunningham, R-Calif., for bribery — McConnell has raised his millions without any evidence of improper personal benefit.

But someone who can raise more than $90 million for his allies — as McConnell did twice, as chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee — is golden when it comes time for GOP senators to elect a majority leader. That’s not counting the millions McConnell sends to GOP colleagues from his own political-action committee and campaign fund.

Some senators shy away from fund-raising duties because of ethical concerns. Top donors tell senators what they want from upcoming votes, and top donors get special treatment, said retired Sen. Alan Simpson, R-Wyo. Their calls to Senate offices are returned first, Simpson said, and their wishes are a priority when action is taken.

“I didn’t enjoy it at all,” Simpson said. “I just felt uncomfortable.”

Yet McConnell never blinks, Simpson said.

“When he asked for money, his eyes would shine like diamonds,” Simpson said. “He obviously loved it.”

McConnell denied that he’s more devoted to money than anyone else “in my line of work.”

“Building up your finances so you can amplify your voice is critical to any successful political activity,” McConnell said. “It’s a central part of the process.”

Still, the symbiosis between McConnell and his donors raises questions about who’s really in charge.

‘A choking sensation’

Take his longtime friendship with cigarette-maker lobbyists, revealed in hundreds of corporate documents made public during litigation. Records suggest a close working relationship behind the scenes.

They instructed him on smoking-related legislation. He offered to amend bills on the Senate floor at their direction. During the 1990s, when he attacked the Food and Drug Administration for its anti-smoking efforts, he followed talking points they fed him. Their attorneys helped draft a bill he filed to protect their companies from lawsuits, as well as his correspondence to the White House to oppose federal smoking-prevention programs.

In turn, they gave him gifts, including Washington Redskins football tickets and many thousands of dollars in speaking fees to supplement his Senate salary. They paid for their own voter polls in his 1996 Senate race, to monitor his progress.

But their real support — millions of dollars in donations — came between important Senate votes. The lobbyists assured him: “We will provide maximum help very early.”

In 1998, McConnell helped to kill a proposal to curb youth smoking. About four months later, he called lobbyists at R.J. Reynolds Co. and asked for $200,000 in corporate “soft money” that he could pass to Republican senators in elections. In an e-mail exchange, the lobbyists settled on “doing an additional 100,000 to him immediately and then seeing what we have left at end of next week.” The $200,000 was more than their company could swallow at once.

“Are you feeling a choking sensation?” Tommy Payne, vice president of external relations, asked John Fish, senior director of federal government affairs, in the final e-mail.

Three months later, rival Philip Morris Cos. sent McConnell $150,000 to distribute to GOP Senate campaigns and $100,000 for his pet non-profit program, the McConnell Center for Political Leadership at the University of Louisville, according to industry and college documents.

McConnell helps people who help him, inside and outside Kentucky. Consider Guardsmark, a Memphis, Tenn., security firm with clients nationwide.

Guardsmark founder Ira Lipman and his employees have given more than $66,000 to McConnell’s campaigns. McConnell has described Lipman as a friend whom he calls to arrange Tennessee fund-raisers.

After the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, demand for private security boomed. Lipman thought it would be useful for his employees to have access to the FBI fingerprint database, then available only to law-enforcement agencies. McConnell co-sponsored the necessary legislation.

“Today our nation is on its way to becoming safer and more secure,” Lipman said in a press release after President Bush signed the bill into law in 2004. And Lipman credited McConnell.

The Inner Circle

Unlike other senators, McConnell, 64, typically avoids the mass fund-raising that brings small donations of less than $200 from working-class Americans through direct mail, phone banks and the Internet.

His donors are likely to start at $1,000. He favors intimate receptions where he can offer them his full attention, leaning in to listen, saying little, holding a glass of wine without paying much attention to it. His Rolodex is one of the best. He is president of the century-old Alfalfa Club, which gathers the nation’s richest and most powerful on the birthday of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, for cocktails and filet mignon.

McConnell seldom opens his own wallet. In the past decade, he has given only $10,000 of his personal funds for campaign donations. Asked to explain that, he pleaded poverty. In his view, it’s wealthier people who support campaigns.

“I don’t have a whole lot of money to contribute,” said McConnell, whose Senate salary is $165,200, and who has homes in Louisville and Washington — the latter a handsome Capitol Hill townhouse assessed at $1.3 million.

McConnell’s invitations to the wealthy to become lifetime members of the “Senate Republican Inner Circle” ($15,000 for life or $2,000 a year) guarantee private dinners and valuable briefings with “the men who are shaping the Senate agenda,” including himself, caucus leaders and committee chairmen.

“Americans are big on rewards these days. Financial rewards in the stock market — cash rewards on your credit cards — luxurious rewards in the travel industry,” McConnell wrote in one invitation. “But a special group of Americans is experiencing one of the greatest reward programs ever, because they took the initiative to become a Life Member of the Inner Circle.”

Those rewards are greatly anticipated by corporate leaders who want a say in Senate decisions. After the Inner Circle welcomed Geoffrey Bible, chief executive at Philip Morris, he sent a copy of the announcement to his aides.

“So now I’m in,” Bible wrote in the margin. “See if we can make the most of it.”

In an interview, McConnell said his invitations exaggerate the intimacy at some events in order to get people to write him a check. A major GOP Senate fund-raiser can draw 1,000 people, he said. No donor ever uses social time with senators to influence Senate business, he said.

“They want their picture taken with you; that’s all it amounts to,” he said.

As McConnell’s influence grows, so does the value of his company.

Lobbyist Kent Hance organized a reception for McConnell in March at the Dallas home of oilman R.H. Pickens. Hance said it raised about $50,000 for McConnell’s 2008 re-election from a few dozen investors and executives. (McConnell spent $5.7 million on his 2002 campaign and already has banked half that sum for 2008.)

Millionaires and billionaires wanted to hear how McConnell plans to further cut their taxes, Hance said.

“He’s gonna be the next Senate majority leader, so we didn’t have to hold a gun on people to get ’em to attend,” Hance said. “Everybody wants to be his friend now.”

Speaking in 1994 at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, McConnell explained his fund-raising: “I prefer to get (money) from individuals who voluntarily choose to give to me because they like what I stand for.”

However, because he now raises the majority of his money nationally, not in Kentucky, it’s not uncommon for his donors to know scarcely anything about him, except that he is a powerful man.

Corporations and professional groups that want a friend in Washington instruct their employees and members to give generously to the rising senator.

At a New York luncheon last fall, McConnell received about $60,000 from scores of workers at two financial giants, UBS and Citigroup, which had just successfully lobbied Senate Republicans for a tough bankruptcy law that makes life harder for credit card debtors.

President Bush praised McConnell by name as he signed the law.

Christopher Hagstrom, a UBS Financial Services securities lender, said managers spread the word to write a check to McConnell. His suggested sum was $1,000, which he gave. Hagstrom said he is barely aware of McConnell, other than “he has the backing of the guys here.”

McConnell has said he encourages donors to send the maximum allowed by law, then arrange for their families to give, too. Before he takes checks from minors, he said, “they, of course, have to be signed by the children.” (It is legal for children to give, if they do so willingly and use their own money, which the Federal Election Commission says is hard to determine.) He gets tens of thousands from donors identified as “students,” usually in sums of $1,000 each.

Pressed for time, McConnell regularly skips daily Senate business. In 2005, for example, he missed 83 percent of his assigned committee hearings about government spending and agriculture. He said it’s “absurd” to question the hearings he misses, given his busy leadership schedule. “Every day is a series of choices about how to spend your time,” he said.

However, he attends myriad receptions in Washington and around the country. These events are scheduled by McConnell’s fund-raising office, run by former banking lobbyist Alison Crombie Kinnahan out of a corporate lobbying firm a quick walk down the street from McConnell’s Capitol office.

McConnell says his coast-to-coast collections are appropriate because he is no longer a mere Kentucky politician. He is “a United States senator.”

Even in Congress, which devotes evenings and weekends to taking money, McConnell is considered extraordinary.

Not physically: Relatively small in stature and with a pale complexion, he is formal and reserved. Other senators cultivate a folksy demeanor to connect with folks back home. Senate aides compare approaching McConnell to meeting a girlfriend’s father.

But he brings in the money. In 2002, GOP senators elected him to their No. 2 post — majority whip — after his record-breaking four years as chairman of their fund-raising machine, the National Republican Senatorial Committee. He’s one of only two senators in decades to serve consecutive terms in the grueling job. In fact, this year, the GOP struggled for months to find anyone to volunteer as chairman for 2008.

Under McConnell, the NRSC paid off a $6 million debt, said former NRSC aide Stuart Roy, who later joined Chao’s Labor Department. McConnell raised $91 million in one term and $96 million in the next.

He disgusted a few colleagues by focusing on televised attack ads. What McConnell calls “amplifying your voice,” others saw as dragging public debate into the gutter.

Many politicians sling mud at their opponents. But McConnell is thought especially brilliant at finding a potential weakness in his opponents, crafting an attack around it and hammering it home, again and again, with blistering commercials — which is where so much of that money goes.

McConnell learned under Republican media consultant Roger Ailes, who handled paid media for his 1984 campaign and is now the head of Fox News Channel.

Not everyone has blessed the approach.

“This nonsense of savaging your opponent and making their noses grow long and their ears grow hairy and big, that’s something my 6-year-old and 8-year-old find quite amusing. It’s great theater, but I don’t know what it does to improve the culture of politics or governance or leadership in this country,” said Sen. Chuck Hagel, R-Neb., in a 1998 challenge to McConnell’s command at the NRSC.

But Republicans stuck with McConnell. He built Senate loyalties by redirecting millions of dollars he raised through his own PAC, dispensing $5,000 and $10,000 at a time. He pledged this year to send $1 million of his funds to pay for other senators’ races.

“His fund-raising is like a corporation, a booming, full-time business,” said Whitman, the former Republican Senate aide.

“He has people in charge of reaching out to new donors, people in charge of massaging the old donors and staying in contact with them, and people in charge of collecting,” Whitman said. “This goes on throughout the year, every year.”

McCain vs. McConnell

In the Senate, McConnell cast himself as the anti-McCain.

John McCain, the once and future GOP presidential candidate, is a fiery reformer drawn to television cameras. McConnell, a defender of the status quo, mocks “reform” efforts with a smirk. He prefers to cut deals in private.

Other senators are wary of butting heads with the media-savvy McCain. Not McConnell. When McCain’s reform proposals displease Republican Party donors, McConnell outmaneuvers the maverick.

“McConnell is not scared of McCain,” said Mark Buse, a former McCain aide for two decades and now a lobbyist. “Because he knows the (Senate) rules better than most people, he does very well by them.”

They have had epic clashes:

* In 1998, McCain pushed a bill to curb youth smoking through new tobacco advertising restrictions.

Senators voted it down after a closed-door lunch for Republican senators in which McConnell — according to news reports — told colleagues that cigarette companies would help them with campaign advertising if they voted against the bill.

Health groups protested that McConnell sold out the nation’s youth.

McConnell refused to publicly discuss his luncheon remarks. But the bill did fail, and federal election records show that cigarette companies poured hundreds of thousands of dollars through McConnell to Senate GOP campaigns.

* In 2000, McCain pushed a bill to outlaw gambling on college sports, which is legal only in Nevada.

Among those arguing for the bill was University of Kentucky basketball coach Tubby Smith, who said Las Vegas bookies legally set the point spreads that form the basis of illegal betting everywhere else.

McConnell was befriending Las Vegas casinos, which opposed the bill. In 1997, he and then-Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott, R-Miss., flew to Las Vegas on the corporate jet of Steve Wynn, owner of Mirage Resorts, to kick off a series of GOP fund-raisers. “We wanted to have support from that industry,” McConnell said later.

They got it. Casinos in the American Gaming Association — whose chief lobbyist, D. Brett Hale, is a former McConnell aide — gave more than $2 million to the NRSC during McConnell’s chairmanship in 1998 and 2000, up from $375,000 for the 1996 races.

McCain’s gambling bill easily passed in committee but languished for four months while he pleaded with Senate GOP leaders to allow a floor vote. They said they could not find time. When they finally agreed to a vote, Nevada’s two senators — both Democrats — were ready to block it with objections. It died.

News reports identified McConnell as one of the senators working against the bill. McConnell recently denied that.

Doris Dixon, who lobbied the Senate for the bill, said McConnell was part of the effort to keep it from getting a floor vote. Dixon was then director of federal relations for the National Collegiate Athletic Association. She said McConnell and his aides refused even to meet with her side.

“Sen. McConnell was instrumental in blocking it from going forward,” Dixon said. “He was talking to other Republican senators about the problems it would pose for him as chairman of their fund-raising committee, which was taking money from Nevada.”

McConnell had pleased his Las Vegas donors earlier by persuading Sen. Dan Coats, R-Ind., to withdraw an amendment that would have ended the federal tax deduction for gambling losses.

The deduction costs the government millions. Coats wanted it replaced with a deduction for Americans who support scholarship programs for poor children. But the gambling industry said the deduction was crucial for its biggest bettors.

* Also in 2000, responding to fatal crashes involving Ford Explorers with Firestone tires, McCain pushed a safety bill to require automakers to report serious defects to the government or risk prosecution.

McCain’s bill passed in committee but stalled when several senators placed anonymous “holds” on it, blocking a floor vote. McCain angrily cried, “The fix is in!” Business groups and Senate GOP leaders backed the shadowy stall tactic.

News reports and McCain’s office identified McConnell among the senators placing a hold.

“I was there, I was intimately involved with lobbying on Sen. McCain’s bill, and Sen. McConnell definitely was actively opposing it,” Joan Claybrook, president of watchdog group Public Citizen, recently said.

McConnell, an advocate of anonymous holds, recently denied placing a hold in that case. He said he and the Senate voted for McCain’s safety bill, and it became law.

However, what really happened — according to congressional records and interviews — is that the Senate killed McCain’s bill by blocking the vote. In its place, the Senate adopted a weaker House bill sponsored by Rep. Fred Upton, R-Mich., and supported by the auto industry. McCain reluctantly accepted it as a compromise.

Critics said Upton’s bill did not require automakers to analyze their data for evidence of defects, and it allowed government secrecy to keep the public from learning of safety problems.

McConnell took more than $75,000 from automakers in the five previous years, according to the Washington-based Center for Responsive Politics. Ford Motor Co.’s Washington advocacy team, which spent more than $8 million lobbying in 2000, was led by Janet Mullins Grissom, who was McConnell’s first Senate campaign manager and chief of staff.

People who know McCain and McConnell say they dislike each other. In separate interviews, the senators were respectful. McConnell said he feels no animosity over their “terrific battles.”

Asked about McConnell, McCain smiled tightly and shrugged. “One thing I’ve learned in politics, I try never to look backwards in anger,” McCain said. Then he turned away.

Enemy of reform

Campaign donations by “special interests” corrupt the Senate, Mitch McConnell warned — in 1984.

As Jefferson County judge-executive, McConnell challenged incumbent Sen. Walter “Dee” Huddleston, D-Ky. He flew to a breakfast at Washington’s Capitol Hill Club to ask the major PACs for money.

They refused. They backed Huddleston. So the underdog bit the hands that wouldn’t feed him.

“Huddleston For Sale to the Highest Bidder,” accused one of his campaign press releases attacking the senator’s PAC and special-interest money. McConnell depicted Huddleston as solely concerned about cash.

Within days of his surprise victory, McConnell launched fund-raising for his 1990 re-election, tapping the very Huddleston donors he had criticized. PACs alone gave him more than $41,000 before he took office.

“There was a lot of atoning to do,” lobbyist Benjamin Cooper told the Herald-Leader during a McConnell fund-raiser, a month after the 1984 election.

In a recent interview, Huddleston said he heard complaints.

“It got back to me pretty quickly,” Huddleston said. “Mitch went to the people who had supported me and told them that if they wanted any kind of representation in the Senate from this day forward, they had better pony up to him, starting now. Open your checkbooks.”

Not true, McConnell countered. He didn’t have to threaten anyone, just welcome them with open arms. It’s common for “special interests” who backed the loser to switch sides after an election, he said.

“I’ve always found it a bit amusing,” McConnell said. “They all have a right to support whomever they choose. And when they’re not supporting you, you have every right to complain about it.”

McConnell continued publicly warning about corruption while privately raising as much money as he could for his first decade in the Senate. Democrats, then the party in power, held the fund-raising advantage. McConnell called for campaign-finance reform to neutralize their edge.

“The electoral process suffers from real and perceived special-interest influence,” he wrote in a Herald-Leader opinion column in 1990.

Everything changed in 1994. Republicans seized Congress. Money shifted to the GOP. And in an about-face, McConnell became Washington’s fiercest enemy of campaign-finance reform.

For years, he beat back McCain and Sen. Russ Feingold, D-Wis., as they tried to ban unlimited “soft money” contributions from corporations, unions and the wealthy. That opposition became his signature issue. Money equals speech, he said, so limiting donations is akin to gagging a political protester.

When McCain and Feingold’s Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act passed in 2002, McConnell called it “stunningly stupid.” He sued all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court to stop it — and lost.

He resents Republican reform sympathizers.

In 1998, Rep. Linda Smith, R-Wash., challenged first-term Democratic Sen. Patty Murray. McConnell’s job as NRSC chairman was to assist GOP Senate campaigns. But Smith called for campaign-finance reform and assailed “the old boys and the old establishment.” McConnell limited her funding to a fraction of the more than $400,000 he was authorized to provide to her. Smith was defeated.

“We ended up with no money to put on any kind of TV or radio advertising,” Dale Foreman, who was chairman of the Washington state Republican Party, said recently. McConnell gave him a frosty reception when he flew east to plead Smith’s case, Foreman said.

“He clearly had strong opinions on campaign-finance reform, and anyone who disagreed with him, Republican or not, was not going to get any help,” Foreman said.

McConnell denied snubbing Smith because she called for reform. He said she simply could not win. “She was never in the game,” he said. But in McConnell’s NRSC fund-raising material sent to donors before the 1998 election, Murray was described as “highly vulnerable to defeat.”

GOP senators were happy to let McConnell lead the charge against reform, freeing them from taking a politically risky stand, said Brian Minnich, a McConnell aide in the 1980s.

McConnell insisted that voters do not care — “This issue, for average Americans, ranks right up there with static cling,” he said in a public television interview — and that was true, at least for Kentucky.

His 2002 election opponent, Lois Combs Weinberg, recently said her polls showed only five percent of the state’s voters objected to McConnell’s opposition to campaign-finance reform.

McConnell’s ardent pursuit of money set him apart and made him a leader. He is baffled by politicians who complain about having to ask for money, said Minnich, now a lobbyist.

“He wasn’t embarrassed by fund-raising,” Minnich said. “And he never forgot the people who helped him. That’s key.”

‘It was thuggish’

Not every donor wants to pay forever. In 1999, a group of prominent corporate leaders — including some of McConnell’s donors — led a rebellion against his fund-raising style. To his great anger, they endorsed reform.

One of them was Edward Kangas, who was worldwide chairman and chief executive of accounting giant Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu from 1989 to 2000.

Kangas was no purist. In 1995, he and other Deloitte executives put together about $20,000 for McConnell. Kangas said Deloitte wanted “visibility” as it lobbied for the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act, making it harder for investors to recover fraud losses. The GOP Congress passed the act over President Clinton’s veto.

Consumer advocates howled, but McConnell backed the act. Arthur Anderson & Co. — the accounting firm later disgraced by its role in the Enron Corp. fraud — encased a copy of the bill in plastic to keep as a trophy. It also gave McConnell $3,000 about the time of the Senate vote.

Sending money to politicians on occasion is standard business, Kangas said. But it began to feel as if whenever Congress met, lawmakers called to mention upcoming votes that could help or harm Deloitte, he said. And a donation request would follow.

“It was a shakedown,” Kangas recalled, declining to say whether he specifically referred to McConnell.

“It’s often a regulated industry, like the banks, the financial services companies, the pharmaceuticals,” he said. “An executive gets a call from a politician — or someone close to the politician, who everyone knows speaks for him — who says, ‘Hey, it would be really appreciated if you could show us some support right now.'”

So Kangas joined other corporate leaders at the Committee for Economic Development — a Washington-based business group — in endorsing the McCain-Feingold campaign-finance reform bill.

McConnell was outraged. He mailed angry protest letters to CED members and their companies to warn that their reform advocacy would crimp the income of the Republican Party.

“I would think that public withdrawal from this organization would be a reasonable response,” he wrote. At the bottom, he scrawled personal messages naming individuals and concluding: “I hope (name) will resign from CED. Mitch.” “Mitch was not completely happy,” Kangas said, chuckling.

“It was thuggish,” said Charles E.M. Kolb, the CED’s president.

Kolb, a White House adviser to the first President Bush and an appointee under President Reagan, previously had donated to McConnell, but he resented McConnell’s tone. His group stood firm.

Continue reading at Lexington Herald Leader.